The following is an article on the Great London Exhibition of 1851 written by Barbara McIntyre that appeared in the Majolica International Society's publication Majolica Matters in the Summer 2001 issue. It gives an excellent framework for the introduction of majolica in England.

I have illustrated, edited and formatted the article for the web for clarity and content.

The Exhibition by Barbara McIntyre

The Exhibition at the Crystal Palace was like a fairy tale come to life. The magic in London that summer of 1851 was tangible. There was national pride, amazement, good fellowship and pure joy. The interior decoration of the Crystal Palace was under the supervision of Owen Jones, an expert in Byzantine architecture and color. The metal framework was painted pale blue and trimmed in yellow. The girders were painted bright red. On the exterior all the participating nations’ flags were flown on poles across the roof.

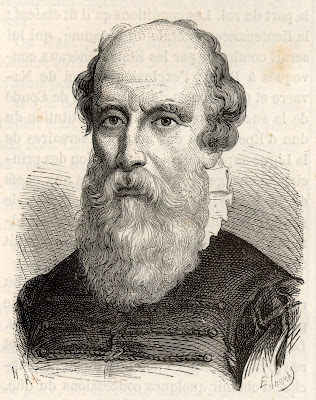

Architect Owen Jones

The Crystal Palace under construction

The Crystal Palace under construction

The exhibits began arriving almost immediately after the completion of the building. The British reserved the western section of the building for its own displays and those of its colonies. The Eastern wing was for foreign product display. Each participating nation had its own display area. An area was reserved for products of China but the Chinese sent no exhibits. The British merchants scoured London to fill the empty space with products from dealers of oriental wares and from private chinoiserie collections.

Season ticket for the 1851 Exhibition

The Crystal Palace with the surrounding grounds

Just before opening day, countless sparrows were found in the trees within the central transept. These birds would undoubtedly soil the patrons and ruin the exhibits. Lord Wellington was consulted and during a visit to view the birds, he suggested that the only way to be rid of them was to import sparrow hawks. It was actually reported that having heard that, the sparrows departed with Lord Wellington never to return.

Crystal Palace interior showing the monumental crystal fountain

Eastern nave of the displays at the Crystal Palace

South Eastern Railway 4-2-0 Crampton locomotive from the 1951 Exhibition

As opening day neared, the Chief Commissioner of Police asked for and received 1000 extra men for crowd control and emergency help in case of disaster. The British were horribly afraid of the hordes of foreign spectators that were expected to flock to the Exhibition. It is also reported that Wellington had 10,000 troops on reserve at a hidden location. None were needed.

Chromolithograph of the opening ceremony to the 1851 Exhibition

Chromolithograph of the opening to the 1851 Exhibition

Her Majesty and her entire entourage opened the Great Exhibition on May 1, 1851. Only those invited guests and those with season tickets to the Exhibition were allowed to attend the opening ceremonies. After Queen Victoria’s entry music ended, Prince Albert, as President of the Royal Commission, thanked Mr. Paxton … rescuer of the entire Exhibition, for his part in the inception of the Crystal Palace. Prince Albert repeated his hope that the Exhibition would further peace and friendship between nations.

Chromolithograph of Queen Victoria opening the 1851 Exhibition.

Her Majesty is said to have attended the exhibition at least twelve times with her children during May and about 50 times in all. Within a few days of the opening, Victoria wrote to her uncle, King Leopold:

“My Dearest Uncle – I wish you could have witnessed the 1st May, 1851 the greatest day in our history, the most beautiful and imposing and touching spectacle ever seen, and the triumph of my beloved Albert. Truly it was astonishing, a fair scene. Many cried, and all felt touched and impressed with devotional feelings. It was the happiest proudest day in my life, and I can think of nothing else. Albert’s dearest name is immortalized with the great conception, his own, and my own dear country showed she was worthy of it."

Quite a bit of what we know about the Exhibition has come from Victoria’s journal entries as well as published reviews. There is a three volume catalog of the Exhibition’s entire contents. Each volume contains 500 pages.

The reviews of the Exhibition were varied, from ecstatic to total pans. In an example of the latter, Jane Welsh Carlyle actually wrote:

"Such a lot of things of different kinds and of well dressed people – for the tickets were still five shillings – was rather imposing for a few minutes; but when you came to look at the wares in detail there was nothing really worth looking at – at least that one could not have see samples of in the shops."

In the center of the Crystal Palace’s transept rose a crystal fountain 27 feet high made by Follett Osler. It contained 4 tons of pure crystal glass. On either side of the fountain were groups of statues by famous British sculptors.

Follet Osler’s monumental crystal fountain, at the center of the exhibition

The center transept also contained the world’s largest organ sent from America. It also housed a circus with a famous tightrope walker.

Tightrope walker The Great Blondin

Advertisement for The Great Blondin at the Crystal Palace

The number of exhibits varies from report to report. Most report the numbering of exhibits from 13,000 to 17,000. Among the American exhibits were the McCormick reaper and the Colt revolver.

United States exhibition

Colt model 1851 Navy Percussion revolver

Colt revolver shown at the 1851 Exhibition.

Colt displayed over 500 guns at the U.S. exhibit

Austrian exhibit

Turkish exhibit

French exhibition

The exhibits ranged from the exquisite Kohinoor diamond to some stuffed frogs in human poses sent by Germany. The frogs were a special favorite of Queen Victoria. Is this why there are so many Majolica designs with frogs in human poses? There were exhibits of lace, fur, hair, fabrics of all kinds, machinery in motion, tools, minerals, railroad engines, steam hammers, arms, tapestry, furniture, carpets, glass, china, and jewels. The list of items on display makes one wonder how many days it would take to view them all.

The Koh -in-noor diamond was taken from India

during the colonial era and presented to Queen Victoria in 1850. It was

displayed for the first time at the Crystal Palace in 1851

Egyptian exhibition

An exhibition of furs

George Jennings built the first "pay to use" public restrooms. It was reported that over 827,000 people willingly did so.

The administration was required to have pure drinking water available to all at no charge. In a reaction to this requirement, the magazine Punch is quoted as replying:

"whoever can produce in London a glass of water fit to drink will contribute the rarest and most universally useful article in the whole Exhibition."

Throughout the entire park there were many other attractions. There was a display of fountains with about 12,000 water jets. There were copies of famous statues from around the world, a model of a lead mine and even replicas of extinct animals such as dinosaurs.

The exhibition of Sweden, Norway and Denmark

The Crystal Palace dinosaurs under construction.

The dinosaurs were moved to Dinosaur Park in 1854 after the

Crystal Palace was reopened as an event park.

Humorous commemorative card from 1851 Exhibition showing

some of the fanciful dinosaurs

More than 6 million people attended the Exhibition during its 141 days. During this same period over 4 million visitors arrived in London. That was twice as many as that period the year before. Foreigners accounted for 58,427 of those visitors with the French and Germans leading the way. Many of the other popular tourist attractions also benefited from the crowd.

Souvenir medal from the 1851 exhibition

Souvenir mug from 1851 Crystal Palace Exhibition

Public admission to the building ended on October 11, 1851. The exhibitors and their friends were allowed to attend on October13th and 14th. After a short closing ceremony at which Prince Albert spoke briefly, the Hallelujah Chorus was played. The Exhibition officially ended.

We remember this exhibition because of Minton’s introduction of majolica ware and also of the displays of Palissy ware.

[Editor's Note: In 1851 the ware we now call majolica Minton called Palissy Ware. Majolica described Minton's tin glazed ware. Refer to the above link for clarification.]

!851 Catalogue showing Minton majolica and Palissy Ware

Minton Palissy Warea group

!851 Catalogue showing Minton majolica and Palissy Ware

Minton Palissy Ware wine cooler

Minton Palissy Ware jardinieres

From "The Crystal Palace, and its contents : being an illustrated encyclopedia

of the great exhibition of the industry of all nations, 1851".

However, the Crystal Palace Exhibition did not particularly increase trade or promote peace and more interaction between nations as Albert had hoped. It did however produce a grand profit of 180,000 pounds. The Commissioners used this money to purchase the land that would be the future homes of the Victoria and Albert Museum, The Science Museum and Library, The National History Museum, The Geological Museum, The Imperial Institute, The Royal College of Science, The Royal School of Mines, The City and Guilds College, The Royal College of Art, The Royal College of Music, The Royal College of Organists and The College of Needlework.

[Joseph] Paxton oversaw the dismantling and re-building of the Crystal Palace at Sydenham, England, a 200 acre theme park, in 1852. Concerts and exhibitions were held there, and it eventually became a sports arena. A television company was established in the south tower, and the nation’s first color television was developed there.

Sir Joseph Paxton c. 1860

Queen Victoria at the reopening of the Crystal Palace as an

event hall, June 10, 1854

In 1936, the Crystal Palace burned to the ground after serving the British for 85 years.

Fire at the Crystal Palace

Fire at the Crystal Palace

Remains of the Crystal Palace after the 1936 fire

Remains of the Crystal Palace after the 1936 fire