If it wasn’t for Léon Arnoux, there would probably be no Victorian majolica.

Joseph François Léon Arnoux was born in 1816 in Toulouse, France into a family of potters. His father Antione owned a porcelain pottery in St. Sernin in Toulouse and had the resources to send his eldest son, Léon, to school for engineering and design. After graduation, Léon began working with his father in St. Sernin but the unstable French political atmosphere and the financial panic that ensued led to the bankruptcy of the pottery. The following chaos of the French Revolution of 1848 led him to leave France and explore the potteries of England. There he toured the factories of Staffordshire studying technique until he eventually landed at Minton.

Arnoux was first hired at Minton as a Superintendent in June 1849 to explore the development of hard-paste porcelain to compete with the work done at Sèvres and Meissen on the continent. His training at Sèvres as an artist and designer as well as work at his father's factory made him ideal for such an assignment. His work impressed Minton sufficiently for him to name him Art Director in charge of both the technical and artistic direction of the pottery. With porcelain development unable to compete with that already in the market he turned his attention to earthenware.

His initial work with earthenware at Minton was on their dust-pressed Prossers Patented tiles.

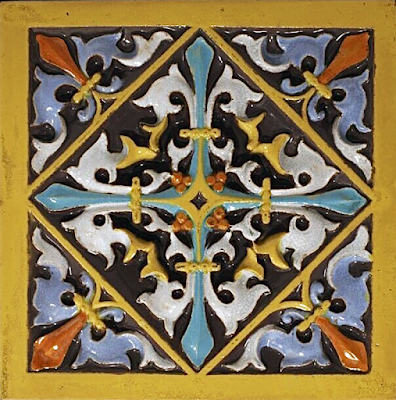

From here he moved onto copying the opaque tin-glazed colored terracotta of the 15th century Italian Renaissance and the work of the Della Robbia Workshop. He accompanied Herbert Minton and Colin Minton Campbell on a trip touring Europe for inspiration on this new line. The tin-glazed ware that resulted he called majolica, a line similar to what we refer to as maiolica today. At the time the term majolica was the standard 19th century English term to describe the highly ornate hand decorated 15th and 16th century ware from Italy, Majorca, France and Spain.

He then turned his attention to the French ware of Bernard Palissy. As a Frenchman he was exposed to Palissy’s work at a young age. His studies in chemistry led to his development of brightly colored transparent high-lead content glazes that were an imitation of the Palissy ware of 15th century France. This type of ware he called Palissy ware. This new glaze differed from the earlier developed majolica in that the tin-glazes used in majolica were largely opaque.

The advantage of Palissy ware was that numerous different color glazes could be applied at the same time to a biscuit ceramic and not require different temperatures for firing different colors. Wedgwood, Whieldon and Greatbach had pioneered this type of multicolored lead glazed earthenware in the 18th century but no other pottery had followed up in this work in the 100 years since its development. The Palissy ware glazes had a higher concentration of lead in the glaze and were applied over highly molded earthenware bodies at relatively low cost producing a finish of high gloss that was appealing to the eye and inexpensive to manufacture. They did not require the expensive decorative work of Arnoux’s tin-glazed majolica.

Herbert Minton was eager to put on an exceptional high profile display that would cement Minton’s place as the premier English pottery. With the 1851 Crystal Palace Exposition just around the corner, Minton and Arnoux devoted all of Minton's resources to combining both majolica and Palissy ware glazes for exhibition pieces for the show. In addition to showing its own display, the Minton factory contributed Palissy ware tiles to the large Pugin designed stove for John Hardman & Co. shown at the exhibition.

Minton's display proved to be a great success. In the words of architect M. Digby Wyatt who assembled an illustrated catalog for the exhibition:

"So free and original is Mr. Minton's version of Majolica ware, that we can scarcely refuse to it the merit of of great novelty. Both in modeling and execution, it is a very favourable specimen of the productions ot his celebrated manufactory…"

In time both Minton's Palissy ware and majolica became known as majolica. Today the tin-glazed majolica is rather rare as it wasn't a success for Minton. The lead-glazed Palissy ware however proved to be a sensation. This new majolica started an international trend in pottery that was to last for over 60 years.

Arnoux remained associated with Mintons for the remainder of his life eventually becoming a partner at the incorporation of the firm in 1885. Even after his retirement in 1892 he remained a consultant with Mintons assisting the company during a financial crisis. His contribution in the development of Mintons’ many lines cannot be overstated. He brought in from France the best sculptors, painters and modelers he could get and created, along with Minton, a school to educate artists in pottery decoration. He even patented a more efficient downdraft oven for firing the ware.

He also developed numerous other bodies and finishes for Mintons that are outside the focus of this blog. For more detailed information on Arnoux's enormous contribution to Minton view this video prepared by the Potteries Museum and Art Gallery. He died in 1902 and is buried in Staffordshire near the Minton factory he devoted his career to.